Trams of route C at Broglie station in the city center. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

Preamble

At the heart of Strasbourg stands the majestic Gothic cathedral, which dates back almost six centuries. This architectural masterpiece, which attracts visitors from all over the world, is, in fact, a reincarnation - it was rebuilt after its predecessor was destroyed by fire seven times. Another symbol of modern Strasbourg has suffered a similar fate - its tram network. Like the cathedral, the first tram system was "destroyed" in 1960, only to be "reborn" in a new, modern form three decades later. This story of destruction and reincarnation is key to understanding the strategic importance of the tram, which has evolved from a utilitarian means of transport to an instrument of profound urban transformation.

Strasbourg Cathedral is the tallest building in the city. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

The example of Strasbourg proves that the restoration of the tram network was not just a transport project, but a fundamental urban and political decision. It radically changed the face of the city, returning public space to the people, reducing congestion and air pollution, and ultimately became a model for many other European agglomerations that sought sustainable development. Strasbourg's success proved that bold ideas, when implemented, can breathe new life into the urban landscape.

To fully appreciate the scale of this achievement, it is necessary to turn to historical background. An analysis of the reasons for the decline of the first tram system and the socio-economic factors that led to its revival allows us to understand the depth of the challenges facing the city and the validity of the strategic choice it made.

Historical Context: Fall and Rebirth

The analysis of the historical cycle of "development-decline-rebirth" is of strategic importance for understanding modern solutions in the field of urban planning. The history of the Strasbourg tramway is a classic example of how technological and social priorities can change, and how the mistakes of the past can become the basis for innovative solutions in the future. Let us consider the reasons for the disappearance of the first tram network and the socio-economic factors that led to its triumphant return.

The Golden Age and Decline of the First Network (1878–1960)

The first tram line in Strasbourg, still horse-drawn, opened in 1878. The system was electrified in 1894, which gave impetus to rapid development. The network grew, covering not only the city but also the surrounding areas on both sides of the Rhine, and at its peak in the 1930s reached an impressive length of 234 km, consisting of approximately 100 km of urban lines and 130 km of intercity lines.

However, in the 1950s, during the post-war reconstruction and the growing popularity of the automobile, the tram began to lose competition to buses and private cars. It was perceived as an outdated mode of transport that interfered with automobile traffic. Eventually, the decision was made to completely eliminate the network. This process culminated in a symbolic act on May 1, 1960: the last tram drove through the city with a black wreath, reminiscent of a funeral procession, marking the end of an entire era.

The era of the automobile and the first steps towards change

The closure of the tram network opened the way for unhindered motorization. By the 1970s, the center of Strasbourg, like many other European cities, was overcrowded with cars. Traffic jams, chaotic parking, and air pollution were a daily reality. Up to 50,000 cars passed through Place Kléber alone every day.

The turning point came under the leadership of Mayor Pierre Pfilmant, who recognized the pernicious nature of this development model. On August 5, 1973, despite strong opposition from shopkeepers and car enthusiasts, the first step towards returning the city to its people was taken: a pedestrian zone was created around the cathedral. "The pedestrian zone that we are opening today is just the first step," explained the mayor. "We want pedestrians to be able to walk in complete freedom, without fear of being hit by a car, and to enjoy the wonder of old Strasbourg."

This step marked the beginning of a long journey towards rethinking urban mobility. The increasing problems caused by the dominance of the car forced the city authorities to seek a radical solution, which led to a decisive choice in the late 1980s.

Strasbourg Cathedral, High Gothic, 14th century. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

Strategic choice: tram vs. metro

In the late 1980s, Strasbourg found itself at a crossroads in its civilization. The choice between an underground automated metro (VAL) and the revival of the surface tramway was not simply technical, but deeply ideological: it was a clash of two opposing visions of the 21st century city. The first vision envisaged hiding public transport underground in order to preserve the dominance of the car on the surface. The second, on the contrary, saw transport as a visible tool for revitalizing public space and completely reorganizing the urban landscape. This chapter analyses the political, financial and urbanistic arguments that tipped the scales in favor of the tramway.

The political battle of 1989

The question of the choice of transport system became a central issue in the 1989 municipal elections. The then centre-right majority, led by Mayor Marcel Rudloff, actively promoted the VAL metro project, similar to the one already implemented in Lille. This idea was supported in particular by shop owners in the city centre, who feared that the construction of an overground tram would lead to long-term inconvenience, a reduction in parking spaces and, as a result, an outflow of customers.

They were opposed by the opposition Socialist Party, led by Katrin Trotmann. Her team, which included future mayor Roland Ries, advocated for a modern tram project, seeing it not only as transportation, but also as an opportunity for a qualitative transformation of the city.

Arguments in favor of the tram: Finance and urban planning

Kathrin Trotmann's team put forward a series of compelling arguments that combined financial pragmatism with a progressive urban vision.

- Economic feasibility: The key financial argument was cost. Building 1 kilometer of VAL metro track cost the same as building 4 kilometers of tram track. This meant that for the same money, the tram network could be much more extensive and cover a larger area.

- Urban transformation: Unlike the "invisible" metro, the tram was seen as a powerful tool for revitalizing urban space. Its construction was inextricably linked to projects of pedestrianization, the creation of new public spaces, and the return of streets to people, displacing excessive car traffic.

- Flexibility and integration: The above-ground system allowed for a denser and more flexible coverage, easily integrating into existing urban development and pedestrian zones. Unlike the metro, the tram could serve not only mainline traffic flows, but also become part of everyday urban life.

Route lines A and D - the first section of the modern tram from 1994. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

The decision and its consequences

Catherine Trotmann's victory in the 1989 elections was decisive. Shortly afterwards, the Strasbourg city council finally approved the tram project: 56 votes in favour to 34 against. This decision marked the rejection of the car-centric model in favour of sustainable, people-oriented development.

The successful implementation of the project and Trotmann’s confident re-election in 1995 sent a powerful signal to other cities in France. Strasbourg’s success proved that the tram could be not only an efficient means of transport but also a guarantee of political victory. This inspired the mayors of Montpellier, Nice, Lyon and other cities to revive their own tram networks, launching a real tram renaissance in France. Thus, the strategic choice made in 1989 went far beyond Strasbourg and influenced the development of urban transport throughout the country.

The modern tram: The backbone of Strasbourg's mobility

Strasbourg’s modern tram network is not just a mode of transport, but an integrated system that serves as the basis for sustainable mobility for the entire agglomeration. It is a prime example of how an infrastructure project can be a catalyst for positive change in the urban environment. This section provides a detailed overview of the network’s characteristics, the stages of its development and its overall impact on the urban space.

Underground tram station “Central Railway Station”. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

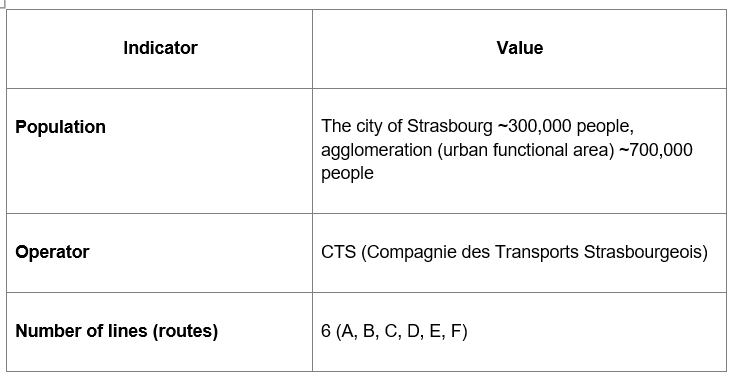

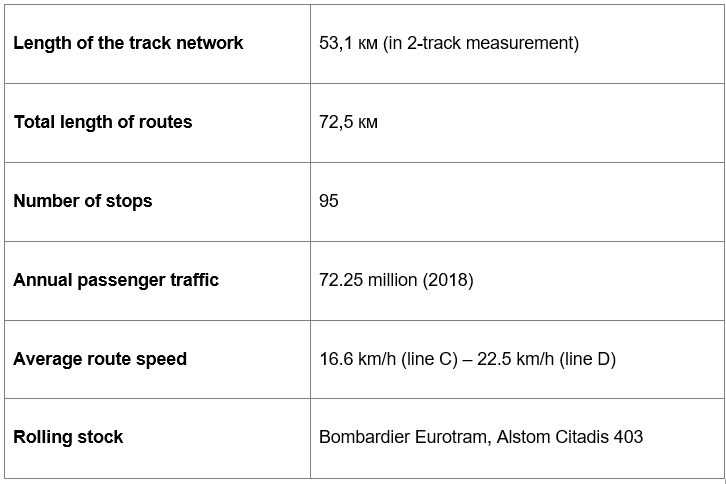

General network characteristics

The network's key indicators (taking into account the extension of line F, opened in November 2025) demonstrate the scale and efficiency of the system, making it one of the most advanced in Europe.

Stages of development and expansion

Entrance to the underground tram station under the railway station. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

The network development took place in stages, allowing for the gradual integration of new lines and adaptation of the urban space.

- 1994: Opening of the first "A" route, which connected the western district of Hautepierre with the southern suburb of Illkirch-Graffenstaden. This phase included the construction of a 1.4-kilometre tunnel under the central railway station and an underground station at a depth of 17 m. To encourage motorists to use the tram, interceptor parking spaces were also built near the stations on the periphery.

- 1998–2000: Launch of routes "B" , "C" and "D" . The first route quickly became overloaded with passengers, so in 1998, with the extension of route "A", route "D" was immediately opened, duplicating "A" with a small branch. Routes "B" and "C" were completed, with a total length of 11.9 km. The central interchange Homme de Fer was formed, which became the heart of the entire network and the station with the largest passenger flow, where 5 out of 6 routes intersect today.

- 2002-2003: Connection with regional railways . The terminus of the A line at Hohenheim was connected to the Strasbourg–Lauterburg line. In Krimmer-Mainau, a railway station was built next to the tram stop of the same name, allowing connections between the A line and the Strasbourg–Offenburg regional trains.

- 2007–2008: Creation of a "matrix" (maillé) network structure . Launch of the tangential line "E" , which allowed passengers to travel between districts, bypassing the central Homme de Fer hub, which significantly relieved it.

- 2010: Launch of the "F" line and another reorganization of the network to improve its efficiency. The tram tracks are used on streets with boulevards, which were previously used by trams before the era of mass motorization and the dismantling of tram lines in the 1950s.

- 2017–2018: Historic network expansion across national borders . Route "D" line crossed the Rhine and connected Strasbourg to the German city of Kehl , becoming one of the few international tram routes in the world.

- 2020–2025: Further expansion to the west. The most significant project of this period is the extension of the "F" line to Wolfisheim, which was completed in November 2025.

Homme de Fer station is a transfer hub in the city center. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

Integration into urban space

The success of the Strasbourg tramway is largely due to its deep integration into the urban landscape. The construction of the lines was accompanied by comprehensive urban projects that transformed the city:

- Large-scale pedestrianization: Starting in 1992, the city center was gradually closed to through-traffic. Streets that were previously heavily congested have been transformed into comfortable pedestrian zones, where trams coexist harmoniously with pedestrians and cyclists.

- Park and Ride (P+R) parking network: A network of parking bays has been created on the outskirts of the city, near key tram stations. This allows drivers to leave their cars at the entrance to the city and continue their journey by public transport, significantly reducing car traffic in the center.

- Development of cycling infrastructure: The construction of new tram lines has been a catalyst for the creation of modern cycling infrastructure. For example, a two-way cycle path has been laid along the new section of the "F" line, ensuring safe and convenient movement for cyclists.

Thus, the success of the tram in Strasbourg lies not only in its transport efficiency, but also in its comprehensive integration, which goes far beyond the purely transport function and forms a new quality of urban life, focused on comfort, environmental friendliness and people.

The multi-section tram easily navigates turns in narrow streets. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

Features of tram infrastructure

The tram renaissance in Strasbourg has led not only to the revival of electric rail transport as a modern urban system, but also to qualitative changes and innovative, and sometimes radical, solutions in the urban and tram infrastructure in particular. Below are some of the features introduced along with the development of the tram.

Tram and pedestrian street - Rue de la Mésange. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

- Tram-pedestrian streets . Most of the streets on which the tram runs in the city center are completely closed to car traffic, or have only 1 lane for access to the adjacent city center development. From private transport, only bicycles have through access, which are given priority on streets with vehicle traffic permission.

- Tram tracks in dense historical buildings . Most lines in the city center run through narrow streets, where even car traffic had to be closed. The distance from the track to the walls of the buildings is from 2 to 5 m, and the sidewalk separating them smoothly rises to the level of the platforms at the stops. At the same time, accessibility for people with reduced mobility is ensured both to the tram and to the entrances to the establishments on both sides.

- Dedicated lane and priority at intersections . Throughout the entire length of the network, the tram runs separately from road traffic, usually separated structurally (by a curb or other surface between the rails, in particular a lawn). At intersections, the tram has special signaling, different from the general traffic rules, and unconditional priority when passing, which allows for a clear schedule and high route speed (up to 22.5 km/h).

- Tram boulevards and narrowing of the carriageway . Tram lines outside the historic city center are laid mainly on streets with boulevards, or where there were previously 3-4 lanes of traffic and wide sidewalk areas. To preserve the boulevards, the carriageways of the streets are narrowed to 1 lane in 1 direction, and the boulevards are additionally used for laying cycle paths and parking.

Boulevard de la Victoire (Victory) with 1 lane in 1 direction. “University” station with an island platform the size of the boulevard. Photo – Google Maps panoramas.

- “Green tracks” . A significant part of the tramway track, both on and off the streets, has a grass surface instead of asphalt or paving stones. Despite the complex concrete structure of the base and superstructure of the track, the space between the rails is filled with fertile soil and sown with grass. This increases the area of permeable pavement, green areas and reduces the area of overheating of the city surface (asphalt, paving stones).

- Stops on bridges over water bodies . Ukrainian regulations prohibit such solutions, but in Strasbourg they were used to save space in the building, convenient approaches from both banks, and the possibility of arranging convenient platforms.

- Island stops between tracks . The use of two-cabin rolling stock with doors on both sides allows stops to be placed both on the sides and in the middle between the tracks, successfully using the tight conditions in the building.

- Complete barrier-free access at stops . The platforms of tram stations are flush with the low floor of the tram, and to compensate for the gaps between the platform and the side of the tram, special rubber thresholds under the doors have been used: you can get into the cabin in a wheelchair without any effort.

- Tram-bicycle-pedestrian bridges . Both on the “D” route across the Rhine to Germany and on other routes to residential areas, bridges have been built outside the street network at river and canal crossings for trams, pedestrians and cyclists only: in essence, bicycle-pedestrian corridors are created along tram lines, bypassing busy highways, enhancing sustainable mobility in all its forms.

- Tram tracks on residential streets and inside neighborhoods on a separate track . For better accessibility and pedestrian safety, tracks often run not on main streets, but inside neighborhoods, as close as possible to dense residential development - the source of passenger traffic.

“Green tracks”, bike path, sidewalk. Route E line near the European Parliament. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

Prospects and future challenges

To maintain competitiveness and a high quality of life in a constantly growing agglomeration, it is strategically necessary to ensure the continuous development of transport infrastructure. Even a successful system such as the Strasbourg tramway needs to adapt to new challenges and the needs of residents.

Planned development projects

The Strasbourg city authorities continue to invest in expanding the tram network, seeing it as a key tool for developing new districts and improving the connectivity of the agglomeration.

- Westward Extension (Line F): The latest major project to be implemented is the extension of Line F to Wolfisheim , which officially opened on November 15, 2025. This extension added 8 new stations to the network and provided convenient transport connections for around 20,000 residents and 7,000 employees in the western part of the agglomeration.

- Tram Nord: An ambitious project to extend the network northwards is currently under approval and aims to improve connections with the municipalities of Schiltigheim and Bischheim. The estimated cost of the 5-kilometre section is €268 million (€56 million per km, comparable to the construction of a high-speed railway), and the city has so far approved a budget of €140 million excluding VAT. This project is the next logical step in creating a coherent and comprehensive transport system for the entire metropolis.

Line C dead end near the train station. Rubber thresholds visible under the tram doors. Photo – https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tramway_de_Strasbourg

Conclusion: Strategic importance for the agglomeration

The revival of the tramway in Strasbourg is a textbook example of successful urban transformation. It is not just a means of transport, but the backbone of the entire urban mobility system and a key instrument in the city's sustainable development policy. Its success is based on three pillars: a bold political decision, deep integration into the urban space and continuous development.

The story of the Strasbourg tram is not simply the return of a forgotten mode of transport. It is a testament to how far-sighted political vision and comprehensive urban planning can radically change a city for the better. Strasbourg’s success has created a replicable model where political will leads to urban transformation, directly inspiring a “tram renaissance” across France. By abandoning a car-centric model in favor of a people-centered approach, Strasbourg has not only solved its transportation problems, but also created a more environmentally friendly, comfortable and attractive living environment. Like its cathedral, the tram today is not just part of the cityscape, but a testament to Strasbourg’s enduring capacity for regeneration.

Tram-bicycle-pedestrian bridge. Tram route E against the background of the European Parliament. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

Seamless switches with flexible tips. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko

Track construction: under the lawn or asphalt – a powerful layer of concrete base. Photo: Yuriy Lozovenko