Ukraine's regulations on tram and trolleybus infrastructure are not similar to the modern approaches and practices of EU countries, but are instead part of the " Russian world " . The differences from the EU are serious and fundamental. As a result, the current regulatory framework hinders the development of urban electric transport or makes projects unreasonably complex and expensive. It is time for Ukraine to replace the post-Soviet regulatory framework with European approaches and international standards.

Representatives of the NGO " Vision Zero " conducted a comparative analysis of Ukrainian norms with the norms of the Czech Republic and Italy, and Switzerland and Poland were used as additional " review " countries.

In Ukraine, as of 2021, there were 18 tram systems with 2,249 cars and 41 trolleybus systems with 3,743 trolleybuses. They have one thing in common - they are all from the USSR and almost all of them are outdated and require modernization and significant investments. This especially applies to the infrastructure (tracks, power systems, depots) and tram rolling stock. They are also characterized by a lack of development - the networks lag behind the growth and development of cities (do not cover new areas), and the number of rolling stock is lower than necessary.

Similar to old equipment, old rails and trams, Ukrainian norms and standards in this area also need to be replaced. These are the conclusions of the comparative analysis carried out by the authors. Ukrainian norms were compared with the norms of the Czech Republic and Italy,

The study found that Ukrainian norms are fundamentally different from the studied EU practices. The differences identified can be divided into four groups:

1. UNJUSTIFIED PROHIBITIONS. Ukrainian directives often do not allow (prohibit) planning, designing, and implementing solutions that work successfully in other European countries, do not cause any harm, and do not lead to accidents or disasters.

2. UNFOUNDED REGULATIONS. Standards that dictate what and how to do, but do not explain why. Ukrainian standards prescribe in detail radii and distances, construction methods and materials, requirements for the arrangement of the contact network and its components, instead of setting target (parametric) indicators.

3. EXCESSIVE RESERVES. Standards that require infrastructure to be designed with a huge margin of safety, speed, or capacity, without compromising on how to reduce construction costs: either we build "with all the money" or we do nothing.

4. TYPICAL SOLUTIONS INSTEAD OF ENGINEERING. Standards require choosing parameters, such as track properties or switch geometry, from pre-calculated tables and templates from the USSR era, instead of performing calculations for a specific project and construction conditions.

Photo: Bohdan Smykov, AlltransUA

Problem 1. Unjustified bans

The first question that arises regarding our standards is why it is often forbidden in Ukraine to build infrastructure in the way it is done in other European countries? It is enough to look at one photo of the trolleybus line in Prague, opened in 2024, to see a whole "bouquet" of violations of the current standards of Ukraine. For example, the horizontal distance from the contact wire to the nearest tram rail of 3.5 meters and the distance from the extreme contact wire to the edge of the sidewalk of 1.5 meters are "violated".

Joint tram-trolleybus traffic can be seen in other cities, for example, on the streets of Milan and Zurich, but in Ukraine, implementing a similar scenario is prohibited by the requirements of the State Code of Ukraine. It is also impossible to design a trolleybus line through a pedestrian zone, say, in the center of Ivano-Frankivsk. Although this is allowed and implemented, for example, in the historic city of Modena in Italy.

Problem 2. Unreasonable prescriptions

When designing tram lines, the State Building Code of Ukraine requires a minimum distance of 20 meters from the axis of a normal-width track (1524 mm) to a residential or public building. Twenty meters is a lot in the conditions of a European city. This means that you can build a tram track only where land has long been allocated for it (empty space), or if you suddenly decide to design a new urban area "from scratch". At the same time, building a tram where it is really needed - in an existing building - will encounter this restriction. This requirement is probably intended to limit the noise and vibration created by the tram and their impact on the structure of buildings and the lives of residents, but technologies that allow for significant reduction of tram noise and vibration have existed for so long that it is difficult to call them modern. In such situations, the European standards of Italy and the Czech Republic regulate the necessary target indicators, namely, threshold values of noise and vibration. Another example of directive regulation is the requirements for the types of rail fastenings to sleepers, the norms for the number of sleepers, transition curves and other similar regulations. This contrasts with the regulations applied in the Czech Republic, which require that tracks be built in a manner and from materials that are capable of ensuring safety, the expected speed and minimal lateral acceleration (shake). Materials, technological solutions, the method of fastenings or the number of sleepers are not regulated in the Czech regulations.

Examples: the city of Lviv needs to restore a short section of tram track on Kopernika Street (photo #1), which was dismantled in the 1980s. However, the current DBN prohibits this due to the inability to maintain a distance of 20 meters to houses. At the same time, in the Polish city of Szczecin, on one of the new tram lines on Krasinskiego Street The distance from the track to residential buildings is less than 5 meters in some places (photo #2). The tram line project includes modern technologies for reducing noise and vibration and replacing facade windows in some buildings.

Photo #1: Lviv streets…

and photo #2: streets and Szczecin. Source: Google Streetview.

Problem 3. Excess inventory

Just as with the construction of city streets with wide lanes and large radii (unlike the EU), the Soviet gigantomania also affected the construction of electric transport infrastructure. As a result, the DBN requires the construction of tram lines in such a way as to maximize the theoretical capacity of the system: maximum radii, minimum single-track sections, large right-of-way, etc., without taking into account the high cost of such solutions and what is called the Cost-Benefit Ratio.

The most striking example of the excessive requirements are the curve radii. According to DBN, the minimum curve radius for a light rail tram is 400 meters (in difficult conditions at least 200), which is unlikely to be possible in an already built urban environment. For comparison, the limit in Italy for a light rail tram is only 40 meters. In Italy, even when building subways, a more liberal minimum curve radius is used, namely 150 meters.

In practice, this means that in Italy (or another EU country) a light rail transit (LRT) line can make a 90-degree turn in existing development, while in Ukraine this is not possible. DBN prioritizes the high theoretical speed of all sections of the line, and does not allow room for adaptation to the environment and taking into account the needs and capabilities of the city. This effectively makes new lines impossible.

| Area | Minimum radii in Ukraine | Minimum radii in Italy |

| Light Rail section | 400 m - normal limit 200 m - in compressed conditions | 40 m - normal limit 25 m - exceptional limitation |

| Regular tram section | 50 m - normal limit 25 m - in compressed conditions | 25 m - normal limit 18 m - exceptional limitation |

| Turnaround rings and depots | 25 m - normal limit 20 m - in compressed conditions | 20 m - usual limit 15 m - exceptional limitation |

Example: The cantons of Zurich and Aargau opened the Limmattalbahn high-speed tram line in 2022, built into the existing spatial conditions. In some places, the line turns at an angle of 90 degrees with a radius of 45-50 meters . The norms of the USSR and Ukraine completely prohibit such projects, because traffic in such areas will be "not fast enough" for us - we need a radius of at least 200 meters. And the "weird Swiss" do not have fences, there are intersections with road traffic - all this is also unacceptable for us.

The light rail in Switzerland has radii of less than 50 m. Photo: Google Streetview.

Another example: the State Code of Ukraine prescribes that new tram lines should be designed as double-track (the permissible share of single-track sections is minimal). For most conditions, this is a reasonable and necessary solution, but not for all. There are lines and there are spatial conditions where predominantly single-track planning is quite justified and allows to provide the required level of service and stay within the budget. There are no such excessive prescriptions in Europe. For example, a high-speed tram line has been built in Lausanne, Switzerland. (LRT) with numerous single-track sections (see photo), similar examples can be found in other cities and countries. Such a "weakness" would not have passed in Ukraine.

A single-track light rail line in Switzerland. Photo: Google Streetview.

The regulatory method of regulation in Ukraine, which dictates excessive parameters and requirements, leads either to unreasonably high costs or to the impossibility of building an electric transport infrastructure. A light rail system (LRT) could be designed in large cities of Ukraine, for example, instead of the metro (another mode of transport regulated by Moscow), but with the current norms this is essentially impossible. It is not surprising that this mode of transport exists only in Kryvyi Rih and Kyiv, inherited from the times of the USSR.

Problem 4. Typical solutions instead of engineering

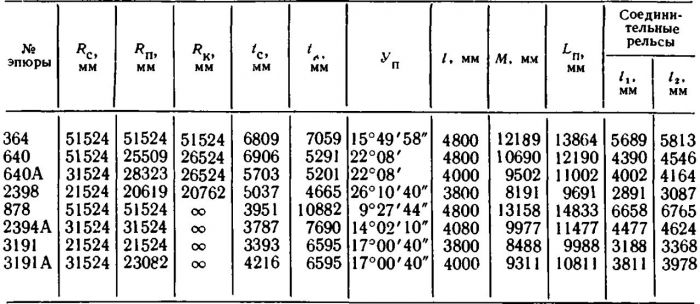

The last group of norms are norms that involve the use of "blanks" instead of applying the intelligence of engineers, software, or world achievements. Instead of setting criteria or targets and limitations for engineers, Ukrainian norms often boil down to selecting numbers from tables. Sometimes these tables still exist in Russian in Soviet documents, and sometimes they are translated and included in DBN and DSTU.

An example of a table of typical solutions from Soviet standards.

The Czech and Italian standards also contain tables, but not to the same extent and for the same purposes as those used in the Soviet school. As a result, the standards in Ukraine provide a very narrow corridor for design without the possibility of creative freedom and individual solutions. The role of engineers, instead of finding solutions and making calculations, that is, instead of engineering work, is reduced to choosing options from blanks that someone made 40 or even 60 years ago.

Conclusions

The regulatory framework of Ukraine is part of state policy. Laws, resolutions of the Cabinet of Ministers, DBN, DSTU, instructions and procedures. If we briefly assess the current state of state policy in the studied industry, we can record the following conclusions:

1. The current regulatory framework of Ukraine as of 2025 does not contribute to the modernization and development of electric transport, but rather hinders it. Numerous prohibitions, restrictions, directives and excessive inventories lead either to a lack of new projects or to an excessive need for space, materials and funds.

2. Ukraine's regulatory framework in this area is significantly different from the practice and norms of EU member states, instead reproducing and imitating the Soviet-Russian school of planning and design and still contains references to dozens of documents approved in Moscow.

3. Ukraine’s archaic and non-European regulatory framework contradicts the goals and strategic measures of the National Transport Strategy of Ukraine and the EU’s Smart and Sustainable Mobility Strategy , in particular those that declare a course to increase the role of urban electric transport and reduce the share of internal combustion engines. Ukraine’s regulations essentially make it impossible to achieve these ambitious goals. If Ukraine really wants to have a chance to achieve its goals, it must modernize its regulations.

Ukraine is a part of Europe, it has long ceased to be a Russian colony. However, in the field of standardization of public electric transport infrastructure, we are still a part of the "Russian world". The transition to European approaches and European standards is not only desirable, but also necessary. Ukraine should continue the transition to a parametric method of standardization in construction instead of the prescriptive (Soviet) method . The first steps towards this reform were taken years ago, even amendments were made to the Law "On Building Standards", but real changes have not yet occurred. Ukraine's full transition to European standards (EN), including Eurocodes, is also a long-overdue and necessary change in state policy, which, unfortunately, is also incomplete. The authors express hope and cautious optimism that political statements about rapid European integration and Ukraine's unconditional European course will be reflected in all areas of state policy, including the one to which our study is devoted.

Note: Regulatory references to the requirements and differences described in the text will be provided in the research report, which is expected to be published in March 2025 on the Vision Zero NGO website .

Authors: Viktor Zagreba and Anton Gagen NGO “Vision Zero”. The article was first published on the “Center for Transport Strategies” portal on 02/28/2025.