Viktor Zagreba and Demyan Danyliuk (non-governmental organization “Vision Zero”) analyze the National Transport Strategy in the context of urban mobility issues.

The new version of the National Transport Strategy of Ukraine (NTSU) until 2030 was approved by the Cabinet of Ministers on December 27, 2024 "under the Christmas tree" without press releases and public comments. As it turned out, the document contains quite a few reasonable and correct assessments and formulations regarding public transport as a component of sustainable urban mobility. At the same time, it leaves the impression of the superiority of form (volume of text) over content, and does not show even an approximate strategic vision of the state regarding the local public transport sector. After all, Ukraine has never had such a vision before. However, the new version of the document gives encouraging signals that changes in the right direction are still possible even in the coming years.

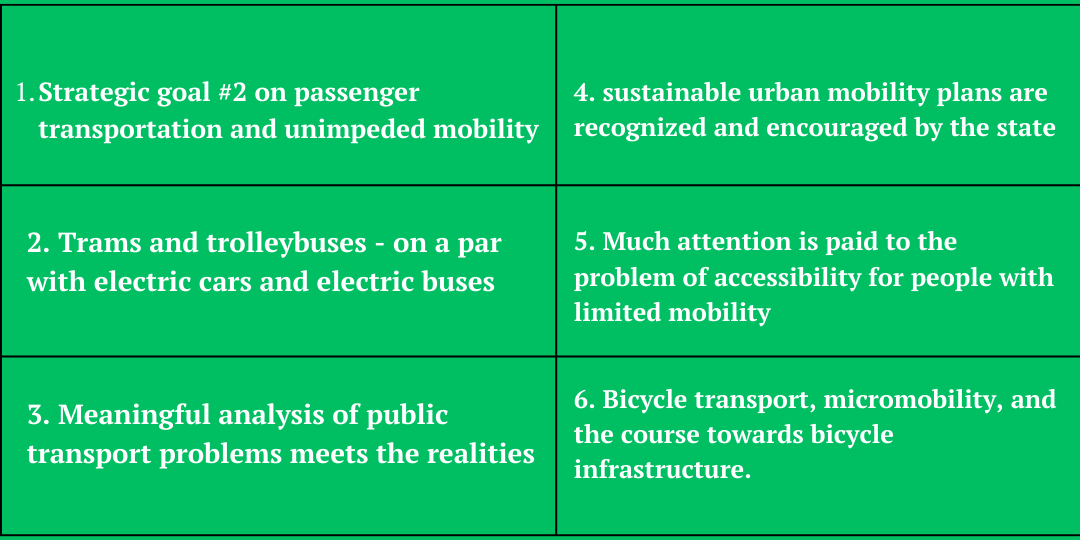

To begin with, let us note several positive aspects that were identified from the official industry document, which relate to public transport (PT) and urban mobility.

Positive aspects of the NTSU regarding public transport and urban mobility

1) "Quality passenger transportation and seamless mobility" are highlighted as a separate Strategic Goal No. 2. This was not at the initiative of the Ukrainian side, but as a direct copying of a point from the "Plan of Ukraine", which clearly spelled out the three goals that the new strategy was to contain.

2) Electric transport - trams and trolleybuses - is present in the document in various parts, and in several cases is listed together with other "green" transport - electric cars, electric buses, and gas-powered vehicles. This combination can be assessed positively, because the trolleybus is the best electric bus!

3) An interesting and broad overview of problems in the field of public transport: problems with route planning, especially suburban ones, the decline and often absence of public transport in rural communities, outdated and small rolling stock, unsuitability for low-mobility groups, etc. The strategy mentions "low quality of transportation" many times.

4) Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMPs), which are not yet included in national legislation but are present in the EU acquis and are the most common planning document, are mentioned and supported. Cities with a population of over 50,000 are encouraged to develop SUMPs by 2027.

5) Physical (in)accessibility of public transport, also referred to in the text as inclusiveness and barrier-freeness, is frequently mentioned. Sentences on this topic are scattered throughout the document - sometimes appropriately, sometimes not.

6) In several places, the NTSU states about bicycles as a means of mobility, the need to develop bicycle infrastructure in and between settlements, which is also needed as a response to the trend of the latest means of micromobility (electric bicycles, scooters, unicycles). These are positive references and the right line of thought.

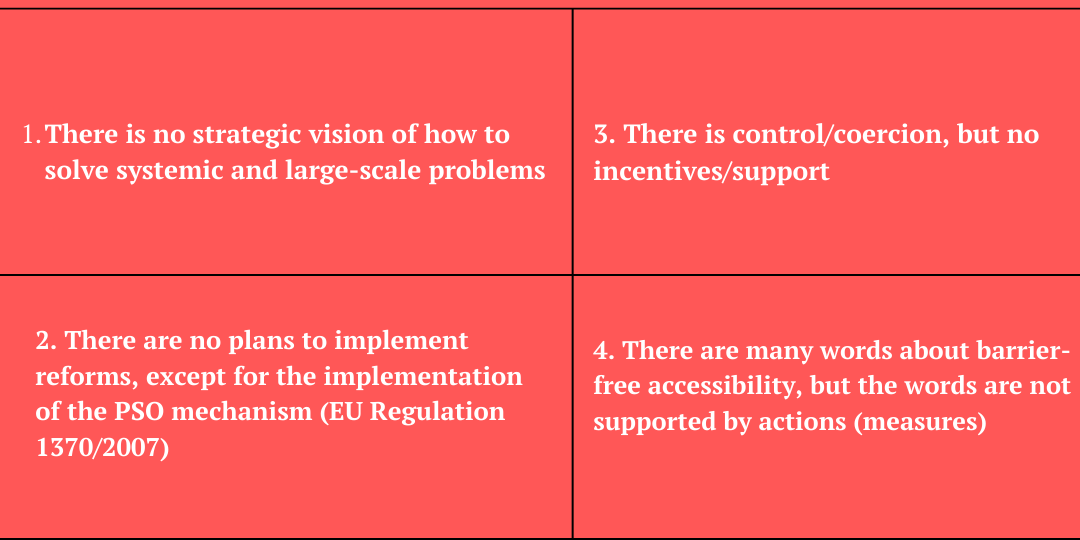

Negative aspects of the NTSU regarding public transport and urban mobility

1) There is no strategic vision of how the state is going to solve systemic problems in the GT sector. The appendix contains several measures, for example, on amendments to the Resolutions of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine of 25 and 15 years ago, but these changes do not have even a theoretical chance of solving systemic problems. The strategy, in fact, does not provide for the implementation of reforms, or even the intention to develop reforms. With one exception.

2) The only reform that can be considered at least nominally is the course for the implementation of the PSO mechanism, however, this reform is also postponed in time by another 2 years. This is a European integration obligation of Ukraine since 2015, which the Verkhovna Rada has not been able to fulfill on time for 9 years and is in no hurry to do so. The Verkhovna Rada Committee has 6 draft laws on this topic pending without consideration, and now the NTSU writes that the Ministry of Infrastructure should develop another one in 2026.

3) The NTSU is trying to add a "stick" to the GT sector (control, supervision, fight against illegal carriers), but there is no "carrot" in sight. Does the state plan to direct part of the future confiscated assets of the Russian Federation to co-finance the modernization of outdated infrastructure (crooked rails, worn-out contact networks, wind and cold in the depot)? Or, at least theoretical intentions to co-finance rolling stock in order to quickly decommission old and inaccessible trams for people with limited mobility? No such intentions have been indicated.

4) Barrier-freeness (accessibility, inclusiveness) of public transport is mentioned in words in many places in the text, but these mentions are not supported by actions. In principle, there are other extensive national documents on this topic, and the measures are described there. However, if the authors of the NTSU mention this aspect so much, then it would be nice to prescribe at least a few strategic measures. There are none.

On the path to quality and seamlessness

Next, we review the description of the problems, objectives and measures of the strategy, evaluate them and try to draw practical conclusions: how can cities and civil society organizations use the provisions of the NTSU as a pretext for advocating for the necessary solutions that strategically benefit the public transport sector? We focused most of our attention on analyzing the content under Goal 2 : "Ensuring quality passenger transport and seamless mobility", although we also review Goal 3, which mentions "decarbonization".

Improving the quality of services

Statements about the "unsatisfactory quality of services" of the transport industry in Ukraine are found repeatedly in the strategy. They say that this is our key problem. Although, is this really a problem, or rather a consequence of other, structural problems? And how to measure this quality of services? The text of the NTSU itself states that in Ukraine there are no criteria for determining quality, and therefore it is impossible to measure and evaluate it. The understanding of the "quality problem" is explained by the authors as follows: " ... passenger transportation is characterized by an insufficient level of quality of services due to the systematic lack of investment, outdated rolling stock, mismatch of bus passenger capacity to passenger traffic volumes, unofficial activities of a large number of carriers, etc. "

Assessment: The authors generally agree with the NTSU that public transport in Ukraine often has a low level, not of "quality", but rather of the level of service (Level of Service). This international concept includes many indicators that measurably characterize the "quality of service" of public transport in any country, province or community: periods and frequency of service, geographical accessibility (% of households within the radius of accessibility to a stop - in Ukraine this is 400 m for cities and 800 for villages), condition and class of rolling stock, availability of low floors, etc. It is possible to measure many of these indicators even now, without making changes to the legislation. But to understand the reasons for this consequence, the strategy did not delve into this, limiting itself to general phrases and hinting that local authorities and carriers are to blame for everything. These are supposedly bad people - they don't invest, their rolling stock is bad, and some even work unofficially. This is similar to the "blame the victims" approach, which implies that the state and its transport policy are not responsible for the deplorable state of affairs in the sector, and therefore the state should do nothing, except, perhaps, force these "bad people" to become good.

Conclusion: the course of the National Electricity Regulatory Commission "for high quality" can be interpreted as meaning that all service level indicators should be measured and improved at all levels where there are gas transmission services. This can be done right now, no special tools are needed for this. Cities and communities can refer to the implementation of the National Electricity Regulatory Commission and write to the President, the Cabinet of Ministers and the Verkhovna Rada with requests to take the necessary actions at the state level. For example, request the abolition of archaic legislative and by-laws, orders, resolutions, norms and standards, demand the early implementation of EU Regulation 1370/2007 on PSO and request the provision of separate lines in the recovery plans (with funds from future confiscated assets of the Russian Federation) for the modernization of the electric gas transmission infrastructure and the renewal of the RS. Urban, town and rural communities can argue that without systemic changes in state policy, they will not be able to improve the level of service, and cities will not be able to come closer to fulfilling the goals of the NTSU. State policy should be based on the goals of the NTSU and maximally facilitate its implementation. Currently, documents approved by the state do not contribute to, but more often hinder, the growth of the level of GT service.

Route problems. The strategy generally mentions systemic organizational problems in the GT sector. It states that: " Management of the development of the transport network ... is not effective enough ... " . The NTSU also writes about the need to " improve connectivity between regions, territorial communities and settlements " , that is, about better connectivity across administrative borders. They also separately mention the forgotten countryside and remote settlements. As the authors of the NTSU admit, the lack of regular passenger transport for some rural residents is a problem of a national nature. In contrast, the NTSU repeatedly mentions the need to organize GT routes from settlements to airports located within a radius of 200 kilometers from them. It is not clear what the state-level problem is with getting people to airports in 2024, when civil aviation has been out of service for three years, the economy has stagnated, the population has shrunk and become poorer. And it is unlikely that the problem of getting from communities to international airports will become acute after the opening of flights.

The tasks in the document are formulated, as usual, abstractly : " improving the network of transport routes... " and " forming an effective network … " ; Transport planning also mentioned abstractly, in epistolary language: the introduction of comprehensive planning for the provision of transport services ... as an integral part of strategic planning for the development of transport in such territories. " The creation of transfer hubs is also mentioned and again the need to provide transportation to airports is mentioned. The NTSU action plan includes the item "Improvement of the regional road transport development system", according to which all regional administrations/public administrations must develop and approve some "regional development programs" for public transport. What is the content of such "programs" if they are not supported by financial instruments? What is the probability that this measure will solve at least some of the systemic problems, and does it make sense to waste the time of regional administrations/public administrations on these formal "development programs"?

Assessment: Suboptimal organization of trolleybus routes is indeed a problem in Ukraine. For example, it is common to see suburban routes overlapped with urban routes, resulting in the movement of "rural" buses to the very center of large cities contrary to the transport policy and planning of these cities, the creation of improvised suburban "bus stations" in city centers, etc. Some cities also have internal problems of conflicting routes, when municipal trolleybuses are completely duplicated by private buses. The authors of the strategy stopped one step short of naming the main problem - an outdated, ineffective and often corrupt route assignment system, which is centered on "competitions" and competition between carriers for passengers, rather than transport planning and coordination.

The list and powers of transportation organizers, the principles of organizing routes, preventing duplication, the list and compensation for "preferential" passenger categories, collection and accounting of payments, mechanisms for co-financing unprofitable routes - all this requires thoughtful and systematic changes in state policy in line with the development of urban agglomeration institutions and inter-municipal cooperation. The organization of routes should be carried out on the basis of real mobility of people and using evidence-based transport planning, and not on the basis of administrative boundaries and outdated "competitions".

"Competitions" should be applied in other industries, such as architectural competitions or competitions for heads of state enterprises - but not to public transport routes. The NTSU does not mention these systemic problems. Instead, it plans changes to the Cabinet of Ministers' resolutions from 2008, 1997 and other years - "improving orders, rules, processes and procedures." Whatever these changes are, they will not solve the fundamental problems of the industry. Figuratively speaking, if a 1989 "Lada" is rusted through and out and outdated, you can, of course, try to boil it, putty and paint it, or you can strain yourself and aim to buy a new (electric) car. All these "improvements" are about painting the "Lada", not about changes.

Conclusion: if we perceive the provisions of the NTSU in an optimistic vein of systemic changes that are needed for a logical, economically feasible and convenient for people system of GT routes, then the implementation of Goal 2 fully deserves support and further advocacy from the communities. The Ministry and the VRU committee, together with the communities and with the support of international partners, could develop a new state policy in the next year or two, based on the experience and practices of Austria, Germany or Sweden. And then make the necessary systemic changes to the legislation and by-laws. The government has surprisingly many resources of international technical assistance available to support the development of such a new policy. However, this requires political will, vision and initiative. Visions of an "electric car", not a "lada". Well, until this is not the case, any initiatives from below to optimize route networks, in particular on the scale of urban agglomerations, can be considered as corresponding to the NTSU. And such optimization processes should be initiated and moved forward, at least on paper, despite the fact that the state is not yet promoting this.

Decarbonization of transport . Combined Goal 3 "Safe, people-centered, environmentally friendly and energy-efficient transport with a course for decarbonization" sets out provisions on the course for "clean transport" - both public and not only. In the language of the strategy, this is called "greening of public and individual road transport". Among the problems, the Cabinet of Ministers stated that "vehicles of carriers and individual vehicles are not sufficiently energy-efficient and environmentally safe", the rapid aging of the vehicle fleet in Ukraine of commercial carriers and private owners. The NTSU writes about the reduction in the number of "environmentally friendly" CNG gas stations.

Assessment . Numerous references to "greening" and "ecology" are a sign that the authors did not "bother" to understand the concepts and distinguish between pollutants (which people inhale and have a negative impact on health), greenhouse gases (which go into the atmosphere and affect the climate) and environmental impact (on the animal and plant world and negative social impact - for example, from road construction). All this is summarized by the words "ecology", "environmental friendliness", which is generally an outdated and unscientific approach.

Conclusion: communities and public organizations can do whatever they want to switch to "ecological" energy carriers for public transport, and this will comply with the NTSU. Environmental carriers in the definition of the NTSU include not only electric current, but also liquefied automotive gases, as well as hydrogen fuel cells. The strategy does not provide for specific reforms or instruments to support this transition. Only one thing is obvious: the purchase of diesel-fueled rolling stock by municipal or private enterprises contradicts the National Strategy. However, at the same time, such purchases are not limited in any way if the buses meet the requirements of "Euro-5".

Cross-cutting topics of the National Transportation Safety Board regarding public transport

Finally, we will describe several high-level questions that arose after reviewing the text and annexes of the new strategy.

1. The compliance of the NTSU with EU strategies is questionable. The preamble to the NTSU mentions that the strategy "takes into account and complies with the provisions" of international agreements and EU documents, in particular the Paris Agreement (climate) and the EU Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy (2020). However, whether this is actually the case and to what extent their provisions are reflected in the NTSU - a comparative analysis can provide the answer. So far, the authors have seen very few similarities between the NTSU and the European strategy.

2. Mixing. In the NTSU, local public transport, interregional, international and even railways are mixed in the same sentences, and from time to time airports also appear. Local public transport should be a separate subject of analysis, strategizing and state policy, and mixing everything in one provision - from rural "minibuses" to future high-speed trains to Warsaw, simply on the grounds that "it all carries passengers" - is counterproductive and illogical. An example from Berlin: the city railway (S-Bahn), metro, trams and buses make up a single system, and their routes go dozens of kilometers beyond the administrative borders of the city. But regional trains and long-distance trains (of various carriers, public and private) - are already a national level of planning and strategizing.

3. Bicycle infrastructure. Bicycle infrastructure has found its serious place in the text of the NTSU, which can be noted positively. Under Objective 2, it is described that: " The level of development of bicycle mobility in Ukraine is insufficient compared to EU member states. According to a Eurobarometer survey, in 2019, 8 percent of EU citizens considered their main mode of transport to be a private bicycle or scooter. It is also mentioned that: " the popularity of other means of micromobility (scooters, electric scooters, unicycles, etc.) has increased. " These correct statements should be transformed into a co-financing program within the framework of the State Regional Development Fund: the state finances, for example, 75% of bicycle infrastructure construction projects in communities.

4. Barrier-free . The NTSU has repeatedly discussed the topic of physical accessibility of rolling stock for people with reduced mobility in various places. This is certainly a big problem, the severity of which has only increased in the last 3 years. So what? In fact, a low floor has long become a "hygienic factor" when purchasing municipal rolling stock: tender documents always require a low floor at least on part of the area. In confirmation of this, the NTSU mentions that 70% of trolleybuses are "adapted to the needs of people with disabilities and people with reduced mobility." But can a person in a wheelchair really get into these 70% of trolleybuses on their own? Hardly. Usually, a trolleybus stops 50-100 cm from the stop platform, often due to the fact that the DBN contains archaic requirements about "pockets", and the driver physically cannot stop the trolleybus right up to the curb. Many of the sentences about barrier-freeness, inclusion, and accessibility sprinkled throughout the text look like artificial flowers – decorative embellishments without practical meaning or strategic vision. The strategy did not address the substantive issues of infrastructure accessibility of the GT.

Authors: Viktor Zagreba and Demyan Danyliuk , NGO “Vision Zero”. The article was first published on the portal “Center for Transport Strategies” on 01/30/2025.